SG7 Pompeii, Tombs at Stabian Gate or Porta Stabia.

Tomb of Cn. Clovatius and gladiator relief. Excavated 1854.

Bibliography.

Avellino F.,

1845. Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano Anno

III, 11 and 12: 1845, pp. 85-90.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum Vol. X, Pars I. 1883. Berlin: Reimer.

Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2004. Pompeii: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge. p. 140; G8.

Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, F111, p. 194.

Fiorelli G.,

1875. Descrizione di Pompei, p. 401,

p. 419.

Fiorelli G.,

1851. Pompei: Illustrazione de' Monumenti, p. XXIII.

Mau, A., 1907, translated by Kelsey F. W. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: Macmillan. p. 430-1.

This is now said to be from SG6 the tomb recently discovered and now attributed to Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius.

On display in

Naples Archaeological Museum. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Tombs discovered by Avellino in 1844.

According to Emmerson, in November and December of 1844, Francesco Avellino excavated the remains of two tombs on the property of Sig. Bertucci, located south of the ancient city.

The first was a rectangular bench tomb.

The second tomb described by Avellino is in truth not a tomb at all, but rather an intricate marble relief that probably once decorated the exterior of a tomb.

See Emmerson A. L. C., 2010. Reconstructing

the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia, Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, p. 78, fig. 1.

See Avellino F., 1845. Bullettino

Archeologico Napoletano Anno III, 11 and 12: 1845, pp. 85-86.

Fiorelli 1851

According to Fiorelli "But of the existence of another exit from the

city on this street, even before the Stabia gate, as well as many local clues,

we must be certain, from that in the direction of the theatres, as I said, a

stone seat of rectilinear shape was discovered, with the inscription in the

back:.

. . . N · CLOVATIO · CN · F · IIVIR · ID · TR ·

MIL · LOC ... (29)

which was then re-covered. The burial place given

to the duumvir by the decurions, must have been one of the most distinguished

of the burial ground, and not confused with the other tombs of the public road,

nor very far from any of the city gates, where those are the most honorable

sites of the Pompeian necropolis. The seat also seems to point to an entrance,

of which others in the form of hemicycles were discovered adjacently to the

western door, in places likewise chosen by the decurions, to give burial to

illustrious citizens. Singular was also that tomb found

near the seat, and described by Avellino (Bull. Arch.

Nap. Tom. 111, pag. 85-90), which was composed of two

large slabs of Greek marble, whose external faces represented in three distinct

areas, a funeral procession, a gladiator fight, and a large hunt (30)."

(29) In addition to the Cloulius

of the consular coins (RICCIO, Mon. fam. Pl. XIV, n. 2). recalled by Avellino (oc p. 86) in comparison with the Clovatius spelling, the

same name CLOVATIVS can be added, graffiti on one of the columns of the viridiary of the house, which is behind that of the great

mosaic, called the laberinto, where also COVLIVS for Cloulius is engraved with V and L in monogram.

(30) Those epigraphs, found before the excavations began, could be believed

to have belonged to this sepulcher; since this stretch of road was very

popular, due to the proximity of the OPVLENTA Salerno, there the rainwater

coming down from the hill, when the road was lower than the present, could have

slightly discovered some ruins of the ancient buildings that flanked it, and

put thus in the open some of those inscriptions, whose provenance is unknown

today.

See Fiorelli G.,

1851. Pompei: Illustrazione de' Monumenti, Proemio p. XXIII.

Square tomb of Cn Clovatius

![SG7 Pompeii. 1883. Inscription as recorded in CIL X.

See Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum Vol. X, Pars I. 1883. Berlin: Reimer.

According to Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss/Slaby (See www.manfredclauss.de), this read –

[C]n(aeo) Clovatio Cn(aei) f(ilio) IIvir(o) i(ure) d(icundo) tr(ibuno) mil(itum) loc[ [CIL X 1065]

Cooley translates the inscription as "To Gnaeus Clovatius, son of Gnaeus, duumvir with judicial power, military tribune; [burial] place [given in accordance with a decree of the town councillors]."

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2004. Pompeii: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge. p. 140; G8.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, F111, p. 194.](tombs%20stabg7_files/image004.jpg)

SG7 Pompeii. 1883. Inscription as recorded in CIL X.

See Corpus

Inscriptionum Latinarum Vol. X, Pars I. 1883. Berlin: Reimer.

According to Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss/Slaby (See www.manfredclauss.de), this read –

[C]n(aeo)

Clovatio Cn(aei) f(ilio) IIvir(o) i(ure) d(icundo) tr(ibuno) mil(itum)

loc[ [CIL X 1065]

Cooley translates the inscription as "To Gnaeus Clovatius, son of Gnaeus, duumvir with judicial power, military tribune; [burial] place [given in accordance with a decree of the town councillors]."

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2004. Pompeii: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge. p. 140; G8.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, F111, p. 194.

According to Mau, "Further from the gate a rectangular seat, probably belonging to the same series of monuments, was discovered in 1854 […should this be 1844 as recorded by Avellino?];

It was built in memory of a certain Clovatius, duumvir, as shown by a fragment of an inscription that came to light at the same time."

See Mau, A., 1907, translated by Kelsey F. W. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: Macmillan. p. 430-1.

According to Emmerson, the first tomb described by Avellino in 1844, was a rectangular bench tomb.

Such bench tombs, which are generally known as scholae, are common immediately outside the gates of Pompeii, although this example is unique in being rectangular, rather than curved.

The dedicatory inscription was carved into the back of the seat, naming the deceased as the Duumvir and Military Tribune Numerius or Gnaeus (the fragmentary inscription shows only an “N" for his praenomen, which, considering the name of his father might have originally been preceded by a "C") Clovatius, son of Gnaeus.

The letters "LOC" are also recorded as part of the fragmentary inscription, presumably the remnant of "locus datus decreto decurionum”, indicating that the place for the tomb was granted to Clovatius by decree of the town council.

See Emmerson A. L. C., 2010. Reconstructing

the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia, Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, p. 78, fig. 1.

See Avellino F.,

1845. Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano

Anno III, 11 and 12: 1845, pp. 85-86.

Tomb with relief of gladiatorial combats

SG7 Pompeii. April 2023. Relief showing gladiatorial displays from tomb at Stabian Gate, inv. 6704, on left.

Looking along “Campania Romana” gallery in Naples Archaeological Museum. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG7 Pompeii. April 2023. Relief showing gladiatorial displays from tomb at Stabian Gate, (inv. 6704).

Now on display in “Campania Romana” gallery

in Naples Archaeological Museum. Photo

courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

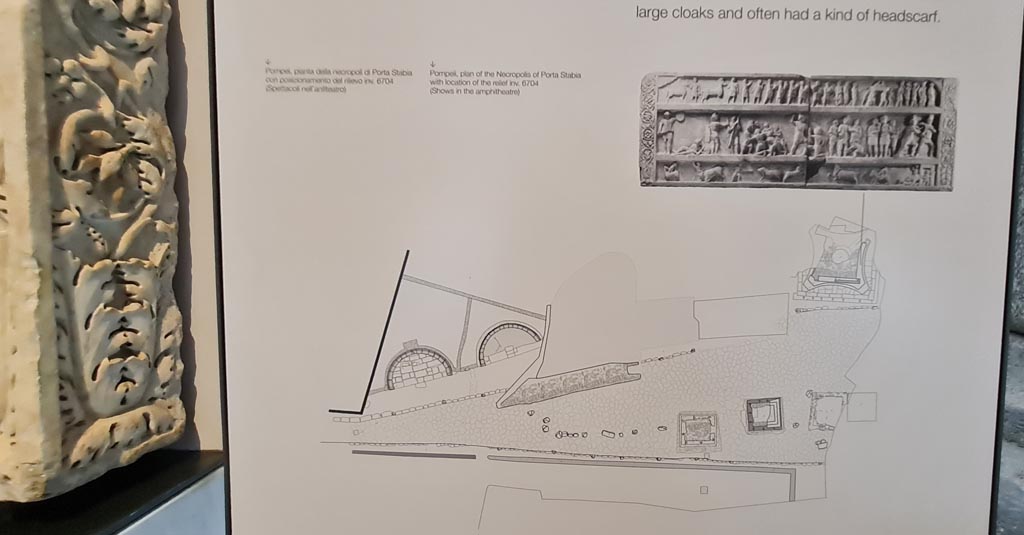

SG7 Pompeii. April 2023. Descriptive card in Naples

Archaeological Museum. This clearly attributes this relief to the tomb of Gnaeus

Alleius Nigidius Maius, tomb SG6.

Photo courtesy of

Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG7 Pompeii. April 2023. Detail from upper row of figures, with figure in toga, in centre. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG7 Pompeii. April 2023. Detail from upper row of figures,

right-hand side. Photo courtesy of

Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG7 Pompeii. April 2023. Detail from middle row, right-hand side. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG7 Pompeii. April 2023. Detail from

lower row. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

![SG7 Pompeii. Drawing of gladiatorial combat relief which Fiorelli says is from the Tomb of Cn Clovatius.

See Fiorelli G., 1875. Descrizione di Pompei, p. 401, p. 419.

"From still another tomb are reliefs with gladiatorial combats, now in Naples [Archaeological] Museum"

See Mau, A., 1907, translated by Kelsey F. W. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: Macmillan. p. 430-1.

According to Emmerson, the second tomb described by Avellino is in truth not a tomb at all, but rather an intricate marble relief that probably once decorated the exterior of a tomb. The relief, which measures more than four metres long and a metre and a half high, shows in three registers from top to bottom a procession, gladiator combat, and a venatio, or staged animal hunt. If this relief is funerary in nature, it is the largest known from Pompeii. Other extant marble funerary reliefs are roughly half this size; the well-known relief that decorates the front of Naevoleia Tyche and Gaius Munatius Faustus' tomb at the Porta Ercolano is just over two metres long.

Unfortunately, Avellino provides little detail on the circumstances of the gladiator relief’s excavation. Although he states that it once decorated the facade. of a Pompeian magistrate's tomb, he does not indicate clearly whether he found the relief in situ on a tomb and subsequently removed it, or whether he discovered it ln a secondary deposit, having been removed in antiquity. The report implies the latter situation, and so we should be cautious in considering the relief a part of the funerary culture surrounding the Porta Stabia: if found in a secondary deposit, the gladiator relief could have originated elsewhere.

See Emmerson A. L. C., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia, Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, p. 78, fig. 1.

See Avellino F., 1845. Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano Anno III, 11 and 12: 1845, pp. 85-86.](tombs%20stabg7_files/image014.jpg)

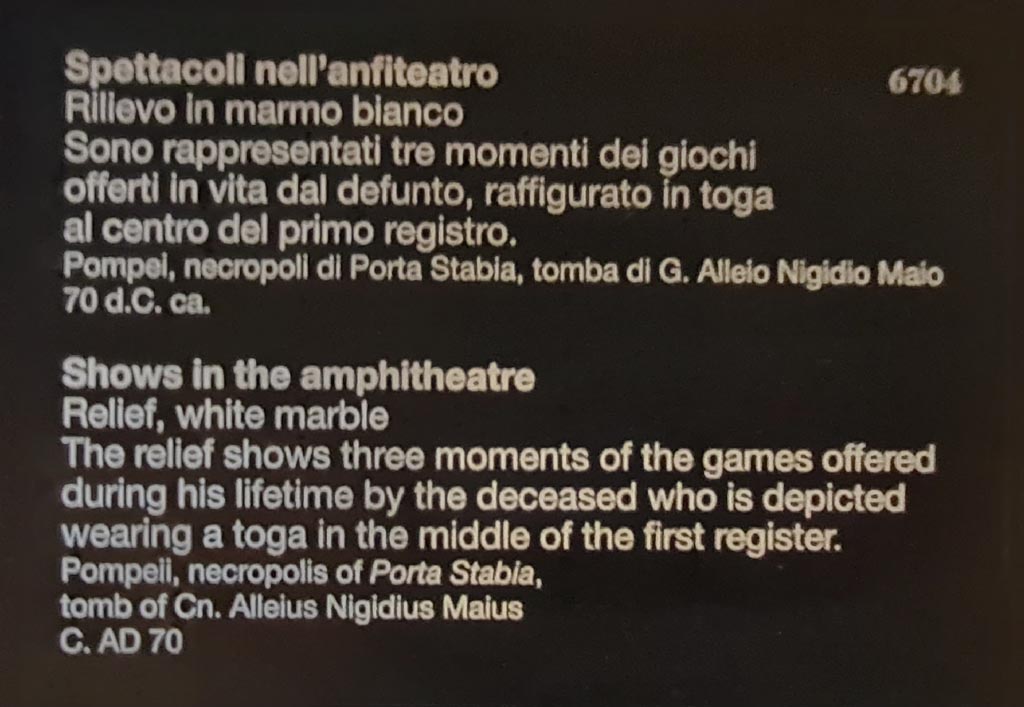

SG7 Pompeii. Drawing of gladiatorial combat relief which Fiorelli says is from the Tomb of Cn Clovatius.

See Fiorelli G.,

1875. Descrizione di Pompei, p. 401,

p. 419.

"From still another tomb are reliefs with gladiatorial combats, now in Naples [Archaeological] Museum"

See Mau, A., 1907, translated by Kelsey F. W. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: Macmillan. p. 430-1.

According to Emmerson, the second tomb described by Avellino is in truth not a tomb at all, but rather an intricate marble relief that probably once decorated the exterior of a tomb. The relief, which measures more than four metres long and a metre and a half high, shows in three registers from top to bottom a procession, gladiator combat, and a venatio, or staged animal hunt. If this relief is funerary in nature, it is the largest known from Pompeii. Other extant marble funerary reliefs are roughly half this size; the well-known relief that decorates the front of Naevoleia Tyche and Gaius Munatius Faustus' tomb at the Porta Ercolano is just over two metres long.

Unfortunately, Avellino provides little detail on the circumstances of the gladiator relief’s excavation. Although he states that it once decorated the facade. of a Pompeian magistrate's tomb, he does not indicate clearly whether he found the relief in situ on a tomb and subsequently removed it, or whether he discovered it ln a secondary deposit, having been removed in antiquity. The report implies the latter situation, and so we should be cautious in considering the relief a part of the funerary culture surrounding the Porta Stabia: if found in a secondary deposit, the gladiator relief could have originated elsewhere.

See Emmerson A. L. C., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia, Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, p. 78, fig. 1.

See Avellino F.,

1845. Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano

Anno III, 11 and 12: 1845, pp. 85-86.

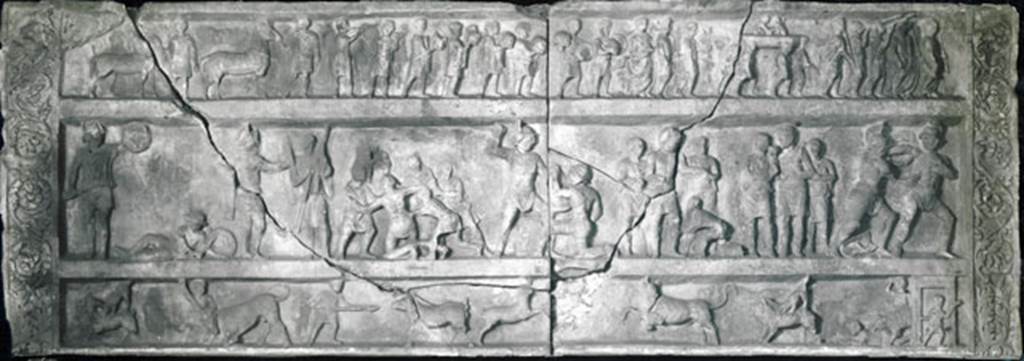

SG7 Pompeii. Gladiatorial relief from tomb at Porta Stabia.

Now in Naples archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6704.

According to Emmerson, this relief measures more than 4 metres long and 1.5 metres high.

See Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia: Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, p. 78, fig. 1.

This has now been suggested it may be part of the tomb at Porta Stabia with the 4-metre-long inscription newly discovered in 2017.

That tomb has been suggested to be that of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius, prolific provider of gladiatorial games and beast hunts in the amphitheatre, like those shown in the relief.

See tomb SG6.

SG6 Pompeii. 2021. Gladiatorial relief with hunting scenes from a tomb at Porta Stabia. The background gives an indication of its large size.

According to Emmerson, this relief measures more than 4 metres long and 1.5 metres high.

See Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia: Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, pp. 78, fig. 1.

According to Osanna, in view of what remains and the visible traces, as well as archive research that is still ongoing, it is more than likely that the top of the tomb SG6, damaged by the construction of the San Paolino building in the nineteenth century, was completed with the gladiator relief preserved in MANN. If you evaluate the role that gladiatorial shows and venations have in praise, it can be assumed that the well-known relief with gladiatorial scenes and hunts with animals kept in Mann was placed there.

The relief has dimensions compatible with the monument SG6, as its length is about 4 metres long, and would respond well in the theme to the role of the deceased as an extraordinary organizer of games.

Moreover, the relief, discovered by the superintendent Avellino in the 1840s, was found out of place (from the damage evidently suffered by the monument in the construction of San Paolino), precisely in the area of Porta Stabia.

Now in Naples archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6704.

SG6 Pompeii.

2021. Rilievo gladiatore con scene di caccia da

una tomba a Porta Stabia. Lo sfondo dà un'indicazione delle sue grandi dimensioni.

Secondo Emmerson, questo rilievo misura oltre 4

metri di lunghezza e 1,5 metri di altezza.

Vedi Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta

Stabia: Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, pp. 78, fig. 1.

Secondo

Osanna, in considerazione di quanto resta e delle tracce visibili, oltre che

delle ricerche di archivio tuttora in corso, è più che verosimile che la parte

superiore della tomba SG6, danneggiata dalla costruzione dell’edificio di San

Paolino nell’Ottocento, fosse completata con un rilievo conservato al MANN. Se

si valuta il ruolo che gli spettacoli gladiatori e le venationes

hanno nell’elogio, si può ipotizzare che fosse ivi collocato il noto rilievo

con scene gladiatorie e di caccie con animali

conservato al Mann.

Il rilievo ha

infatti dimensioni compatibili con il monumento SG6, lungo com’è circa 4 m., e

risponderebbe bene nel tema al ruolo del defunto di straordinario organizzatore

di giochi.

Inoltre, il

rilievo, scoperto dal soprintendente Avellino negli anni ’40 del XIX secolo, fu

rinvenuto fuori posto (per i danni subiti dal monumento evidentemente per la

costruzione di san Paolino), proprio nell’area di porta Stabia.

Ora al Museo archeologico di Napoli. Numero di

inventario 6704.

Bullettino Archeologico

Napoletano XLVI (11 dell’anno III)

Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano XLVI (11 dell’anno III) 1845

p. 85.

Bullettino

Archeologico Napoletano XLVI (11 dell’anno III) 1845 p. 86.

Bullettino

Archeologico Napoletano XLVI (II dell’anno III) 1845 p. 87.

Bullettino Archeologico

Napoletano XLVI (11 dell’anno III) 1845 p. 88.

Bullettino Archeologico

Napoletano XLVII (12 dell’anno III)

Bullettino

Archeologico Napoletano XLVI (12 dell’anno III) 1845 p. 89.

Bullettino

Archeologico Napoletano XLVI (12 dell’anno III) 1845 p. 90.